Donor-derived tumour, kidney transplantation, FISH, cancer, nephrectomy.

INTRODUCTION

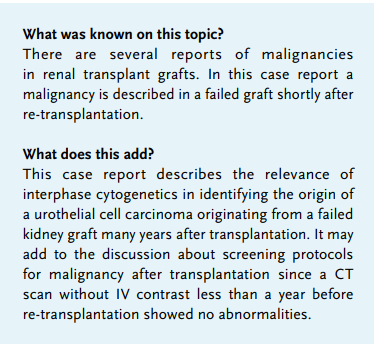

After kidney transplantation, there is an increased risk for development of urothelial cell carcinomas including graft tumours.1 We present a case of a male recipient with two consecutive kidney grafts in which a donor-derived urothelial cell carcinoma in the first graft and in the bladder was found harbouring a XX genotype, as detected by FISH, thus indicating that the tumour originated from the maternal donor.

Apart from a report identifying Y-chromosome status in female post-transplant non-small cell lung carcinoma patients2 and two cases of sex chromosome discrepancy in kidney transplantation patients with urothelial carcinoma,3,4 to our knowledge, there are no other reports after organ re-transplantation about late-onset tumours where the origin of the tumours from donor cells was proven.

CASE REPORT

Nine months after kidney transplantation from a 59-year-old female, a 47-year-old man was seen in our outpatient nephrology clinic for a regular check-up. In the last few days, the patient had developed macroscopic haematuria. His medication consisted of tacrolimus, mycophenolate, metoprolol, felodipine, enalapril, and atorvastatin. The patient used no alcohol or illicit drugs and had smoked 20 cigarettes a day for the last 17 years.

Medical history included end-stage renal disease probably due to hypertension in 2006, followed by transplantation of a kidney donated by his then 70-year-old mother with immediate graft function. In 2012 graft function deteriorated due to membranous glomerulonephritis. In January 2013, the patient was re-transplanted pre-emptively with a kidney from another living donor. Prior to re-transplantation, computed tomography (CT) scanning of the first kidney graft showed no abnormalities.

The patient had no other symptoms besides haematuria. There was no dysuria, no fever and no weight loss. Physical examination revealed no abnormalities. The urine showed > 200 erythrocytes/ µl without dysmorphic erythrocytes, 51-140/µl leucocytes and a 24-hour urine collection showed 0.24 g/l protein with a creatinine of 11.1 mmol/l. A urine culture showed no bacterial growth. The serum creatinine was stable at 136 µmol/l.

The patient was referred to a urologist. A cystoscopy was performed and showed a papillary lesion on the left posterior bladder wall, without lesions around any of the four ureteral ostia. CT-intravenous pyelogram showed shrunken native kidneys and a tumour in the renal pelvis of the first kidney graft without lymph node metastasis. The functioning graft showed no abnormalities.

The patient underwent transplantectomy of the failed first kidney graft. The kidney graft showed a high-grade pT3 papillary urothelial cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis with infiltration into the kidney, however not in the ureter.

Because of the malignancy, immunosuppression was tapered to tacrolimus monotherapy, after a biopsy of the functioning kidney graft was performed and showed no signs of rejection. A transurethral bladder resection (TUR) showed a pTaG2 papillary urothelial cell carcinoma of the right posterior bladder wall.

Chromosome copy number analysis of the explanted graft and bladder tumour by FISH using a chromosome X and Y probe mixture (Aneuvysion Multicolor DNA Probe Kit, Abbott Molecular, Hoofddorp, NL)5 showed malignant cells with a XX genotype and no Y chromosome, indicating that not only the graft tumour, but also the bladder tumour originated from cells of the maternal donor kidney (figure 1). Subsequent screening of the donor was negative for urothelial carcinoma.

The patient was treated with epirubicin instillations of the bladder. Two months later, a cystoscopy showed no abnormalities. Six months later, ten small papillary urothelial cell carcinomas were removed from the bladder wall, again with XX genotype, followed by new prophylactic epirubicin instillations. During the next year, the patient received multiple epirubicin instillations and underwent regular cystoscopies, which showed no recurrences. The patient remained on tacrolimus monotherapy with stable kidney graft function (creatinine 130 µmol/l).

The patient was treated with epirubicin instillations of the bladder. Two months later, a cystoscopy showed no abnormalities. Six months later, ten small papillary urothelial cell carcinomas were removed from the bladder wall, again with XX genotype, followed by new prophylactic epirubicin instillations. During the next year, the patient received multiple epirubicin instillations and underwent regular cystoscopies, which showed no recurrences. The patient remained on tacrolimus monotherapy with stable kidney graft function (creatinine 130 µmol/l).

DISCUSSION

This case shows a patient who received a living related donor kidney from his mother and subsequently developed urothelial cell carcinoma in that graft kidney and in the bladder, after he had already undergone a second transplantation because of graft failure. We provided evidence, using XY-specific FISH analysis of the malignant cells, that both the original tumour and the recurrent bladder tumours originated from cells from the maternal graft.

Current literature does not recommend standard imaging6 or transplantectomy without a clinical indication after graft failure,7 which might have improved the prognosis of this patient. The decision regarding transplantectomy before a re-transplantation is complicated. Careful consideration of the advantages and disadvantages for the individual patient is needed. Our patient was re-transplanted pre-emptively. It was decided not to perform transplantectomy, because this would have led to a period of dialysis and possibly more operative risks and also possible HLA immunisation against the new donor.

Screening for tumours in a failed graft and transplantectomy of a first graft before re-transplantation remains a difficult issue. In our clinic, CT scanning of the abdomen without IV contrast in the preparation before re-transplantation is a standard procedure. The CT scan without IV contrast preceding re-transplantation showed no abnormalities of the first kidney graft. IV contrast is relatively contraindicated for many patients with a kidney graft. The relevance of regular screening with ultrasound and/or PET-CT in early detection of renal graft tumours is also unclear. In our centre, we generally remove failed kidney grafts when patients are dependent on dialysis and have oliguria. In other centres, the failed graft remains in situ. Hence, with regard to transplantectomy of failed kidney grafts, there is also no consensus.

In conclusion, we have proven the relevance of interphase cytogenetics to identify the origin of a tumour in organ transplant recipients, especially after re-transplantation with two donor organs in situ. At this time, the value of screening for graft tumours is unproven.

DISCLOSURES

All authors declare no conflict of interest. No funding or financial support was received.

REFERENCES